Meet Our Guest With Sara Adami-Johnson

Image: Portrait of Sara Adami-Johnson.

Sara Adami-Johnson is a Canadian-based high net-worth (HNW) planner specialising in complex international estate matters involving art and digital assets, family governance and business succession planning. Currently, she is the Vice President of High Net-worth Planning at RBC Wealth Management. Amongst many other distinguished accolades, Sara has completed a PhD, at the International School of Management in Paris, a Masters in US Law, at George Mason University and was called to the California State Bar in 2021.

As GWA continues to develop its own expertise in estate planning for artists and collectors, we jumped at the chance to ask Sara about her experiences in the field.

Welcome, Sara. You’ve been working at the intersection of art and law for several years now. What led you down this path?

I would say “in the beginning there was passion,” a curious lure to the beautiful and complex art world, filled with creativity, talent, opacity and risks.

My “origin block” is in my teenage years spent in Milan, Italy, following in my grandmother’s art buying-spree footsteps, learning the “process,” from research to auction day. Keeping to her mentorship, I acquired an “aesthetic posture,” experiencing the excitement of the arrival of art catalogues in the mail, spending hours researching objects’ history, pedigree, and artists’ lives, dissecting the meaning of paintings’ compositions or the intricacies of hunting-sceneries on silver teapots, scavenging for out-of-the-ordinary, maybe a bit shocking, taxidermied birds or manipulated bones, understanding the value of an item’s condition. And then feeling the thrill of bidding and the reward of ownership when we hopped on the train back home carrying the precious bounty in boxes, or crates.

In my legal studies, the attraction to all that is artistic or collectible led to an appreciation for artists’ rights, and for collectors’ risk management. It was a natural progression: from the artworks to the externalities of art, and the intricacies of law. After all, this space is Janus-faced, on one side we have an art world and on the other a market.

Today, this mix of cultural legacy and my legal background helps me tremendously in approaching planning for clients, setting up an ordinate, logical approach to discuss the art collection and its details; and crafting a framework for having great succession’ conversations.

Art is a personal affair that can be elegantly staged, by constructing an estate plan that is well-thought-out and smartly designed from a family governance, tax and probate perspective.

For those in our audience who may be less familiar with estate matters involving art and digital assets, can you tell us a little more about your role at RBC Family Office?

I can happily say that I have been onboarded to my dream job within a dream team. My wealth planning position is an uber specialised one, working alongside other more wholistic subject matter planners, investments advisors, trustees, insurance and banking colleagues.

The role entails guiding clients through their international art collection and digital asset footprint and assessing where things are at.

Specifically, I go through a granular discovery-disclosure step to establish who is the collector, and what kind of art collection(s) or digital assets we are dealing with. Where is the client resident and domiciled? This determines the law applicable to the estate plan. Who does in fact own the collection, the patriarch in their own single name, jointly between spouses, the family business or trust? Clarity on ownership, on title, opens the doors to explore what kind of planning can be done and whether succession is already embedded into a specific legal structure.

The second step is then assessing the state of collection management. Is there a catalogue? When was it last updated? Does it contains all the required data about provenance, authenticity, condition, insurance, storage information and cost bases? In what format does it exist (paper, excel, software based)? Is it easily accessible and is there a backup? Do the heirs and or the executor/trustee know its whereabouts? More times than not I see either an absence of inventory, salient gaps of recorded information, or an obsolete medium that will create issues for the heirs and estate administrators.

Of particular importance is the geotagging of art assets: the place where the items in the collection are physically located will determine “situs” and the applicable law for tax, estate and family law purposes. The outcomes of this analysis will map cataloguing actions and steps within a timeline for remediation.

Once this preliminary requirement is checked out, then we can start looking at planning wishes. Who may get what? If a daughter gets the collection, then what should the son receive? And how can we optimise the transfer of capital assets to the beneficiaries (by minimising gift tax, estate costs, probate fees and keeping the family harmony).

There is a sort of mixology happening in this phase, where we leap into understanding family dynamics, art valuations and leveraging traditional estate planning tools, such wills, trusts, SPV’s (special purpose vehicles) with an eye to efficiencies and fairness.

Some collectors have public donations aspirations or dreams to institutionalise their collections by creating their own private museum, while others recant to the “let’s sell it all now” posture, in which case we need to pivot and look at how to go about divesting.

What are some of the unique aspects of planning for alternative assets?

One often overlooked detail is “storytelling” statements regarding the “why” the collector bought certain pieces, based on aesthetic preferences. This want of intention and background about the collection leaves a sad void over the very personality of the collector. After all, what we buy tells a lot about who we are; even if Coase’s saying is true “if we torture the data long enough, it will confess.” Not explicitly writing or recording the raison d’etre for a collection robs the heirs of the opportunity to create a “family vernacular” to be proud of, and to (maybe) continue, to understand oneself through it. These stories may also help with adding colour to the art items and possibly their financial value.

No one collector/client is the same. Especially as of late, when we see younger generations being attracted and devoted to amassing significant amounts of luxury items as collectables (from sneakers, to handbags to NFTs). These eclectic types of collectors pose new challenges in the transfer of more traditional collections.

Hence, it’s important that families get together and have the infamous “death talk” to be on the same page.

Why is it important for those new to art collecting to pay attention to estate matters?

I would posit that all collectors should have a bespoke art estate plan and that it’s never too late to start, unless it is too late (if you lose capacity or die without planning).

Otherwise, the community and the society they live in will prove a pre-made plan. It may not be the “best” possible plan, however.

In simple words, not sitting down to discuss and write an explicit will, is a plan in itself, because the existing estate law of the country of the collector’s domicile will operate at her passing as a “default” set of rules (intestacy). So, by putting in place her own rules of engagement for the legacy transfer, a collector makes the choice to “opt-out” of the already existing laws, within the allowed legal limits.

That said, there is further devilry in the details when planning. Especially when it comes to taxes at death (every country has its own rules and regulations). The executor is personally responsible to account for all capital items, attesting to their costs and fair market values for tax and probate purposes. Missing such data is a real problem which will cost the estate time and money and potentially cause frictions, disappointment or stress between beneficiaries if a substantial part of the liquid estate is used to pay government debts instead of being distributed, or if art works or digital tokens are lost, missing or mistakenly valued.

Like any other habit, collectors should establish a disciplined documenting hygiene so that as soon as an item is bought, its details are catalogued, receipts are recorded etc.

If we think about all the passion and money spent in accumulating those special items throughout the years, the real question becomes, why not plan for them?

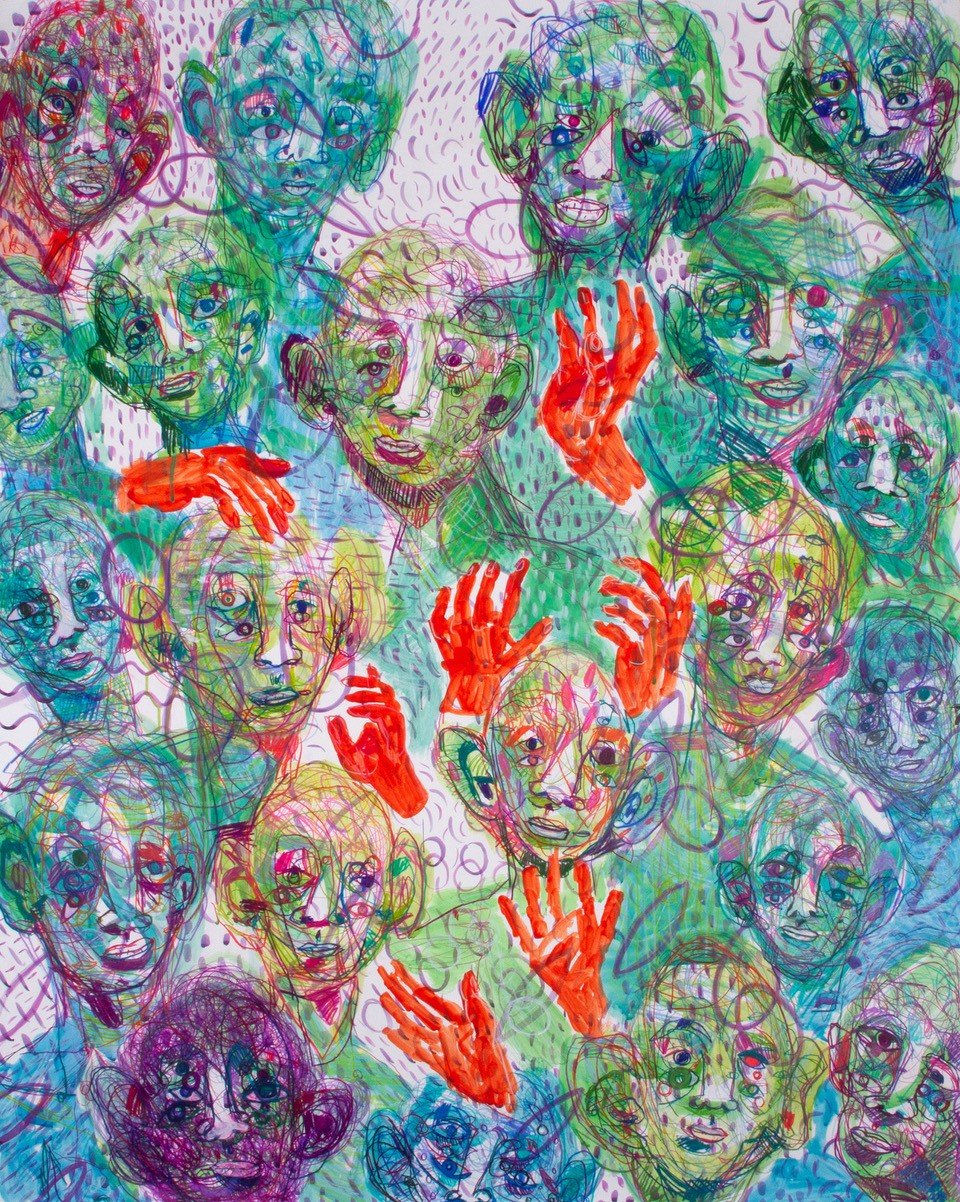

Image: © James Gilbert, courtesy of the artist, Los Angeles.

I understand you’ve worked with artists and advised them on their estates too. Can you tell us a little more about what your role entailed?

Artist’s legacy planning requires a somewhat unique approach, because it entails separating the artists’ “life work” (or what I sometimes refer to as the “business of art”) from the artists’ collection. All artists make work, which forms their art inventory. They also create ephemera that accompanies the items, such as sketches, diary entry, mock-ups, studies, drafts, blueprints, notes etc. There may also be information about the art or about how the artist feels, what they are perceiving and thinking, life’s events etc. Finally, artists are also often collectors of other artists’ works or collectibles, as sources of inspiration, artwork swaps or for pure joy and love of the pieces. Therefore, an artist’s estate plan is multi-faceted as it must address each of these very different categories.

The principles we explored for discovery and cataloguing in the context of art collectors are similar for artists in that, there is no short-cutting. If anything, the amount of art works to be accounted for and their whereabouts may be very complex and depends on how organised an artist is (and if they have any staff at their studio in charge of tasks like organising logistics and contracts). Sometimes, it is problematic to record where painting X is. Is it in the studio, storage or on consignment? Or is it “en route” between places? And care of whom, a gallery, museum, or a collector? Was the work sold with an assignment of copyrights or with a limited personal use licence? Is there a complete history of all the exhibitions and fairs an object may have been shown at? Are there ongoing negotiations or commitments for the donation of art works? Are royalties’ payments are outstanding (whether those be NFT royalties or royalties which the artist is entitled to by law)?

Artist estate planning could be a daunting exercise, especially if only tackled toward the middle to end of one’s career, with many art items spanning multiple years and moments. I would say, artists should start getting their “things in order” from the beginning, apply a workable inventory and business tracking system. As most art schools unfortunately do not incorporate any of this into their programs, I recommend that artists seek out this information with trained professionals during the early stages of their career.

Speaking of digital assets, what does this phrase entail?

The digital assets universe brings its own nuances for planning. While the basic tenants are similar (such as ownership, inventory, wishes, wills and trusts solutions), the actual nature of such assets does present an added complexity.

Digital assets encompass a very broad category of tangible hardware (such as the actual smartphone, tablet and Alexa) and intangible virtual “things”, from email, online banking and social media accounts, to cryptocurrencies, avatars and land in a metaverse.

In addition to one’s own estate planning, the digital service providers and marketplace platforms’ own terms of service may ultimately determine which law applies to the account, whether arbitration is the only available dispute resolution available or where a company can be sued. Another potential conflict issue is posed by platforms’ “Inactive account management” or Legacy tools.

Those are account profile preferences which allow a subscriber to appoint a “nominee” (at times up to 10 people) who, after the passing of a certain amount of time (from 3 to 18 months), will receive an email and gain access to your “inactive” account, either to shut it down or to download content. So, what if you have named your tech-savvy 8-year-old nephew as your inactive account manager, but your executor is your wife or professional trustee? Who is responsible if the account is shut down too soon or accessed and data inappropriately disseminated, or the inactive alert emails are deleted, not actioned?

There needs to be elegance and coordination in digital assets planning to avoid the loss or misuse of data. In particular, planning for cryptographically-based tokens revolves around inventorying their type (for example, whether they are fungible vs non-fungible, whether there are blockchain rails, or they are deployed by a DAO), analysing the type of control (is it custodial or cold wallet access, are there private keys or seed phrases, and is it a multi-sig (multi-signature) or MCP (multi-party computation) wallet?) and the private key’s whereabouts (a safety deposit box in a bank or at vacation home overseas?).

Some extra care should be placed into documenting the type of ownership of keys (single name, or joint), their location, and the collector’s wishes over how a token should be used (is staking of NFTs desirable? Who should vote with the DAO token? Can the executor or heir sell the land in Sandbox?).

Importantly, all those details should not be placed in the will (as it is a public document after one’s death). They should be recorded in a secret document, such as a Letter of Wishes or an Access Guide, designed to be left behind to help the executor find, manage and then distribute the assets.

Recently, I had an interesting conversation about planning around privacy and putting “rails” on the future AI development and use of the testator’s own image, likeness, and voice recording by their heirs. How would you feel about your heirs taking your selfies and holographically augmenting them, scanning your voice and reproducing it algorithmically so that a “digital version” of yourself can continue chatting with your grandkids a decade after your death? And what if it weren’t your family but a corporation doing that?

One sobering point to consider is whether your chosen trusted executor/trustee has sufficient technical knowledge to administer an estate with digital assets and if the beneficiaries want to receive the asset in-kind or in the equivalent in “fiat” (as not all heirs believe in, understand or want crypto assets). These are real conversations happening today.

What are your three top tips for artists and art collectors on what they should be doing now, to better preserve their legacies for the future?

Firstly, think of your art collection as not only a financial asset but also an emotionally-charged part of your persona and net worth. It is something of importance that deserves to be uniquely planned for.

Secondly, don’t turn a Nelson’s eye on your art collection. Incorporate your art legacy within the conversations you are having with your family members – who likes/want what? Who would want to keep what? Who wants to be the steward of your art legacy and how do the heirs feel about the art collection? In my experience collectors are so focused and passionate on their collecting that they can be blind to what their heirs may think of it.

Thirdly, cultivate a liking for cataloguing and documenting. It is not too late to record a measurement, an authenticity certificate or receipt, or the location of your private keys, until it is.

Guest Work Agency provides estate planning advice and archiving consultation. If you are an artist or art collector interested in planning your estate or creating a will please contact us at info@guestworkagency.art.